Betty Friedan coined the term “the Feminine Mystique” to describe the ideal woman of the ’50s, educated or not, as one whose main fulfillment was marriage and family. Sociologist Mirra Komarovsky described the “best-adjusted girl” this way: “She is intelligent enough to do well in school but not so brilliant as to get all A’s … able to stand on her own feet and earn a living but not so good a living as to compete with men; capable of doing some job well but not so identified with a profession as to need it for her happiness.”

What was a bright, independent Stanford woman to do in the face of this ideology? Alumnae from the Classes of ’57 and ’58 shared their experience with the Stanford Historical Society in interviews conducted in 2007 and 2008 as part of its Oral History Program.

Some of the stories are disheartening:

JULIE OLSON BRAMCAMP, ’57, recalled a meeting she had with a journalism professor:

“‘Well,’ he says, ‘Miss Olson, we have found that women who majored in journalism are wasting their money and our time. All you women do is get married and have babies. So I would recommend you find another department.’”

SHARON HARRIS GRAY, ’57, remembers coming to Stanford precisely because it was coed and had a great engineering school:

“I came here because in the fifties, it was very impossible for a girl to get into an engineering school, especially if she wanted to be an electrical engineer. MIT, Cal Tech, none of these were open to girls. And yet Stanford was a coeducational school and had a very fine engineering department. So I came here and I wanted to be EE, but when I told Elva Fay Brown, who was our dean of women, she agreed that I was fully qualified and my test scores were certainly all high enough. But she said I would be taking a highly competitive position away from the head of a family and she could not recommend it. This upset me to no end.”

The interviews include funny stories about curfews and dress codes, mostly about getting around them. There also are stories of forward-thinking scholars.

Olson recalls that after her dreams of studying journalism were thwarted, she continued to work for the Daily, and she found a home in a new field.

“I was taking two units in Central American literature – something that was going to get me an A. And the guy teaching it was named RONALD HILTON. And he gets me after class and he says. ‘Have you considered changing your major and coming and majoring in my program?’ He was putting together his own little empire. It’s a multi‐discipline deal, which was innovative in those days, and in fact is an excellent way to do things. So he’s combining geography, history, literature and language in the study of Hispanic America and Spain – Hispanic American studies. Well, actually I was pretty interested in Mexico, certainly, and pretty much naive in thinking, oh, well, you know, this is going to be the coming thing in the future. We’re going to have North and South America much more involved economically, and perhaps – well, not politically – but just in the sense that they’re going to coexist. And because these guys over here didn’t want me, but this guy here is inviting me. So I’m going to major in that.”

To read more stories, download the PDF: Aspirations and Restrictions: Stanford Women in the Fifties.

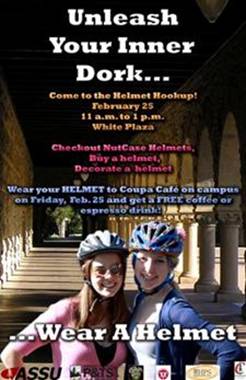

“Unleash your inner dork” and “Love coffee: Love your brain” are slogans for today’s Helmet Hookup, an event designed to promote the benefits of wearing a bike helmet.

“Unleash your inner dork” and “Love coffee: Love your brain” are slogans for today’s Helmet Hookup, an event designed to promote the benefits of wearing a bike helmet.